Post One: I Am But Mad North-North-West. When The Wind Is Southerly, I Know A Hawk From A Handsaw.

Collin McIntyre and Billy Driscoll were the best of friends. They had been best friends for years and years and years. At least in their minds, it had been that long. Billy and Collin were thirteen and so had been friends for years if you did not go back too far.

The boys were adventurers and amateur spelunkers and loved tramping about the island in places they ought not to be—places that were dangerous.

On this day, Billy and Collin were out adventuring in the deep woods of North Island when it began to snow. It was very early for snow and cold weather. Autumn was only a few weeks old, but their island, a dot fifty miles off the coast, was not a place where anything, especially weather, was predictable. The snow was welcome at first. Maybe there would be a snow day at school tomorrow. So the boys marched on, not noticing the flakes falling faster and harder.

About an hour into their hike, Collin looked up and said, “Hey, Bill, where are we? I don’t recognize any of the trees, and we’ve lost our trail.” This was very weird to Collin because they had been taught well by their fathers about tracking. They had been over every uninhabited inch of their island and could tell one trail from another, one nearly identical tree from another, just by looking at the lichens that grew on it. They could tell what part of the island they were on by the smells in the breeze.

Billy had been tracking a deer for some time, a large, heavy buck by the looks of its tracks, and was so engrossed that he did not hear Collin speaking to him.

Collin raised his voice. “Billy, stop tracking that stupid deer and listen to me. Do you recognize this part of the forest? Because I don’t.”

Billy, who was as good a woodsman as Collin, looked up at him and said, “C’mon, Coll, we could blindfold each other and find our way home. For Christ’s sake, we could smell our way home. Whaddya mean you don’t rec…” and then his voice trailed off because he realized with a nauseating pain in his gut that Collin was right.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In another part of the forest, not too far away from the boys, stood another tracker, confused and a little sick to his stomach.

Edgerton Alchurch, MD, island doctor, had been tracking a deer, a deer whose tracks told him that it was a big buck. For more than an hour he had followed it, never seeing it, and now he was more than a little frustrated. The newly falling snow was not helping as it covered the tracks he was following.

So when he decided that the buck would have to wait until tomorrow, he stopped and looked up for the first time in some twenty minutes. He propped his shotgun, a Belgian Browning that had been his father’s, against one of the trees and tried to get his bearings.

Dr. Alchurch, except his years spent in college, medical school and a stint in the USMC as a surgeon during Operation Desert Storm, had spent his entire life on North Island. Indeed, he’d been born in a cabin that had stood not too far from where he thought he was. The problem he had at that moment was that he did not know where he was. For a man who had spent many a day hunting in these very woodlands, that was a very disconcerting feeling.

Then Dr. Alchurch smelled burning oak and hickory. When he looked above the tree line, he saw, through the falling flakes, smoke rising in a column as if from a chimney.

This gave him a small sense of relief. The trees were still unrecognizable, and in his agitation, he did not stop to think that there shouldn’t be an inhabited cabin anywhere near here. He picked up his shotgun, walked forward in the direction of the smoke, and in a few minutes, came upon a cabin identical to the one in which he’d been raised.

Alchurch looked at the cabin, perfect in every detail, and felt a tightness in his chest. His family’s cabin had burned down many years ago, the victim of a forest fire started by lightning. Even the top layer of the foundation stones was eventually carted away for other uses.

He approached the cabin’s front porch, the supporting beams of which had been hewn from felled trees, stripped of their bark, and used in their natural shapes. Alchurch put his left hand on the front door and pushed it open. There never had been a doorknob or any lock on it. His family lived out in the woods, after all.

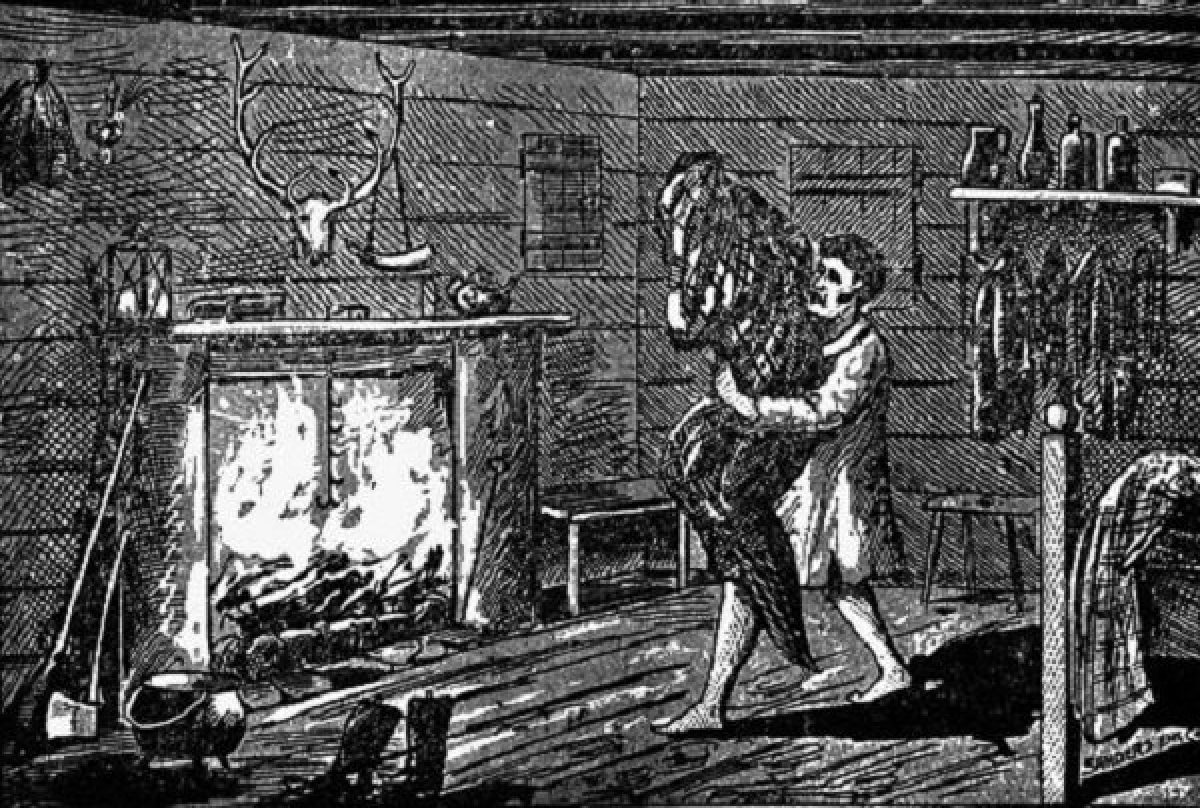

As the door opened, Dr. Alchurch saw the crackling fire, the table set for dinner with the enameled steel plates his mother had used for years.

In the center of the table was a fresh venison roast. In three bowls arranged about the roast were potatoes, carrots, and turnips, all grown by the family.

Dr. Alchurch put his shotgun up against the wall by the doorway, where it had stood for years when he was a child. He walked over to the chair that had been his when he was a boy and sat down.

The fire crackled and popped, the smell of venison wafted to his nose, and then he saw her. She stood in the space between the kitchen, with its woodstove cooker, and the room where Alchurch sat.

You Can’t Really Go Home

The figure of Edgerton Alchurch’s mother stood before him, looking as warm and loving as he had remembered her to be.

Alchurch sat in the chair, rigid and speechless, looking at his mother’s face. He did not know if he should be scared or happy. The figure of his mother made not a move toward him. She looked at him and smiled. Alchurch could feel the warmth of her smile, and he began to cry, letting out a pain that had been fermenting for some fifty years.

“Son, my son.” Alchurch heard words from the figure of his mother, though her mouth did not move. The loving gleam in her eyes never changed.

“My son, I have always been with you. Your father has always been with you.” With that, Alchurch’s father appeared behind his mother. His father was not smiling but rather had a look of absolute peace and understanding.

Alchurch heard the voice of his father the same way he had heard his mother. His mouth did not move. His tones were loving and gentle but also strong, solid, filled with purpose. “You came here not by accident, my dearest son. We brought you here, both of us, to give you our message.”

So far, Edgerton Alchurch had been silent, not knowing what to make of any of it. Now he spoke. “What message, Father?” was all he could manage.

His mother’s voice said, “Billy needs you. Do you understand?”

“No. No, I don’t. I don’t know a Billy. What do you mean? Wait—do you mean the Driscoll boy?”

Instead of answering, Mrs. Alchurch simply stood in the doorway, saying not a word.

Alchurch looked at his father. “Father, what does any of this mean?”

His father spoke without a muscle in his peaceful face moving a fraction of an inch.

“Soon you will understand.”

“Father, Mother…” He could not say another word.

The figures of his parents started to grow diaphanous. He stood and shouted, “No! Don’t go! I’ve waited so long. I’ve missed you both so much.”

“My son,” his mother said, “we will always be with you. We have never left your side.”

His father said, “Be strong, my son. Our departure was necessary for you to become the man you are now.” And they were gone.

The cold Darkness had taken note of what had just happened. This must not be, thought the Darkness.

Edgerton Alchurch stood in silence as the figures of his parents faded from his sight. From the fireplace, a flaming log rolled out onto the floor and across the small room, stopping just under the heavy curtains at the front of the house.

In seconds, the curtains were ablaze. Smoke filled the room. Alchurch made for the door, but as he got to it, the door slammed shut and would not open. He pulled with all of his strength. In a minute he was overcome by the smoke. He slumped to the floor as the cabin burned around him.

Alchurch opened his eyes. They stung as if irritated by smoke. He was on his back, his shotgun by his side, and could see snowflakes drifting lazily down through the branches onto his face. He should have been cold but wasn’t. He should have been sore but wasn’t. He should have been dead but wasn’t. He could not remember how he had gotten there.

Dr. Alchurch stood up feebly. Through his stinging eyes, he looked about him to see his familiar forest. This brought him an overwhelming sense of relief. He saw the trail that he knew so very well being quickly covered by the falling snow. That did not matter. He could see the trees, and they were familiar friends. He could get home from here.